“Nature dictates everything, all activities: health, productivity, mobility, life, and death. One must learn to commune with this reality wholeheartedly, and to do so with humility, with respect, and with gratitude—and if you can do that, you will be able “listen” to it and to learn.”

— Laura Anderson Barbata

Laura Anderson Barbata the opening of Singing Leaf, 2023. Photography by Jacob Holler.

About

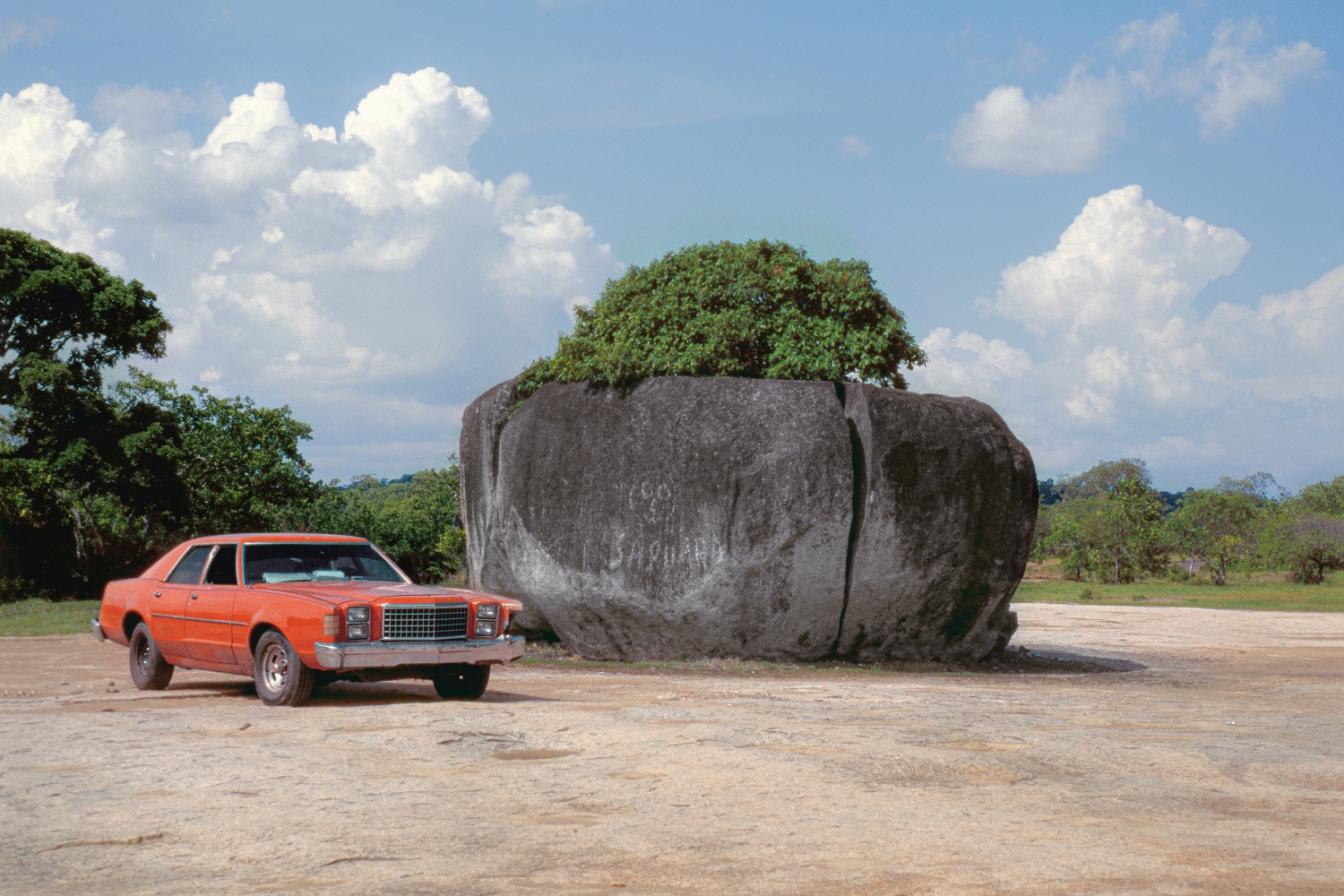

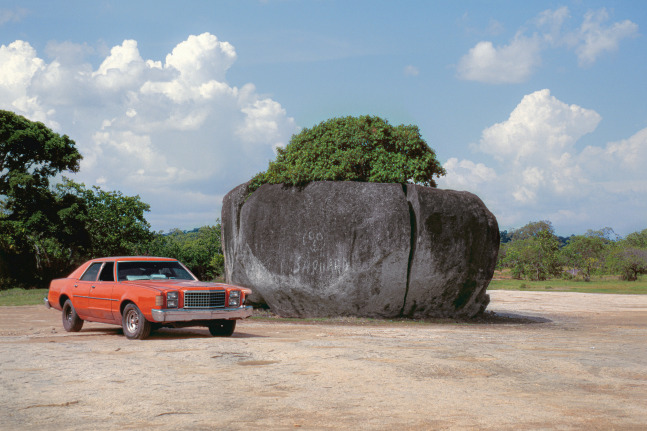

Since the early-1990s, Laura Anderson Barbata has initiated art-centered projects in the United States, the Venezuelan Amazon, Trinidad and Tobago, Mexico, and Norway which emphasize reciprocity, shared knowledge, and decolonial thinking. In 1992, Anderson Barbata, already a practicing artist, traveled to the Venezuelan Amazon, where Indigenous Yanomami, Ye’Kuana, and Piaroa communities accepted her proposal to initiate various papermaking projects. One of such projects is featured in Singing Leaf. Produced with the Yanomami using paper made from indigenous fibers and dyes, Shapono (conceived in 1992 and completed in 2001) tells the story of the community’s first communal dwelling, called a shapono. It was among the first (if not the first) post-colonial accounts of Yanomami folklore made for and by the Yanomami and written in their native language. To this end, paper—particularly handmade paper—had been, and continues to be, central to Anderson Barbata’s practice—both as a preferred medium and a vehicle for storytelling and empowerment.

The impact the collaborations in the Amazon had on Anderson Barbata, both as an artist and a person, would be profound. In the following decade, Anderson Barbata traveled extensively between the Amazon and her studios in New York and Mexico City, creating her work almost in tandem with that she had been making with the Yanomami, Ye’Kuana, and Piaroa communities. Informed and affected by her experiences, she created works in response.

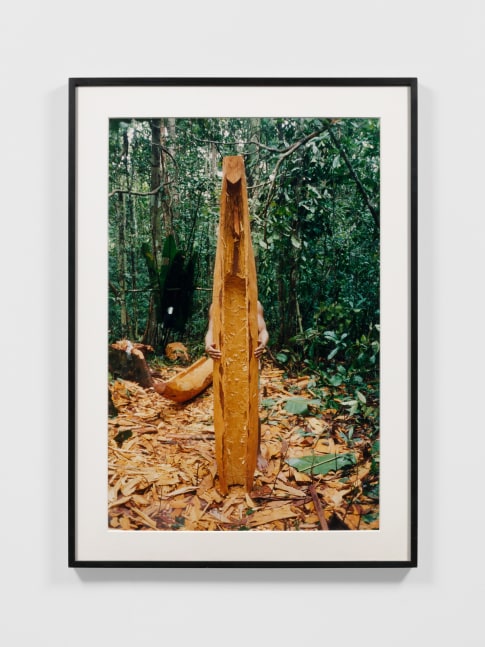

Not only would her work in and related to the Amazon inform future projects, they spurred the artist to produce a series of headless “self-portraits” (some of which incorporate bridge and canoe motifs) in which she radically reconsiders ideas of perception and self-awareness and -reflection. The artist recalled: “I understood who I was and what I was experiencing: that I cross a bridge, my life, without a head because what guides me is not my head nor my eyes, but my inner self, which has its own way of seeing and its own way of thinking. That way of seeing and thinking is going to ensure that I do not fall from the bridge, and I arrive to the other side without falling. I understood that to be able to see the world, I had to remove my head.”